Specialty and High Purity Chemical Supplier, Manufacturer

and Chemical Services

We Enable the World's

Greatest Innovations

We Enable the World's Greatest Innovations

Specialty and High Purity Chemical Supplier, Manufacturer and Chemical Services

Solutions for Specialty Chemicals and Manufacturing Services

Our Chemical Services team of experts have been collaborating with customers for 45 + years in order to bring innovative, chemical solutions to many industries and detailed analysis to a multitude of applications. We provide technical capabilities and expertise needed for all your unique chemical, material Application, Formulation, and Analysis. As a result, we have a strong understanding of new and continued development of the best materials required for robust process systems and finished goods.

Our experts provide the guidance to meet all your unique material needs including, but not limited to:

- Inorganics

- Metal Salts

- Ceramics

- Reagents

- Evaporation

Materials

- Rare Earths

- Alkoxides

- Intermetallics

- Metals

- Pharmaceutical Intermediates

Infinite

Custom Solutions

SPECIALTY AND HIGH PURITY CHEMICALS

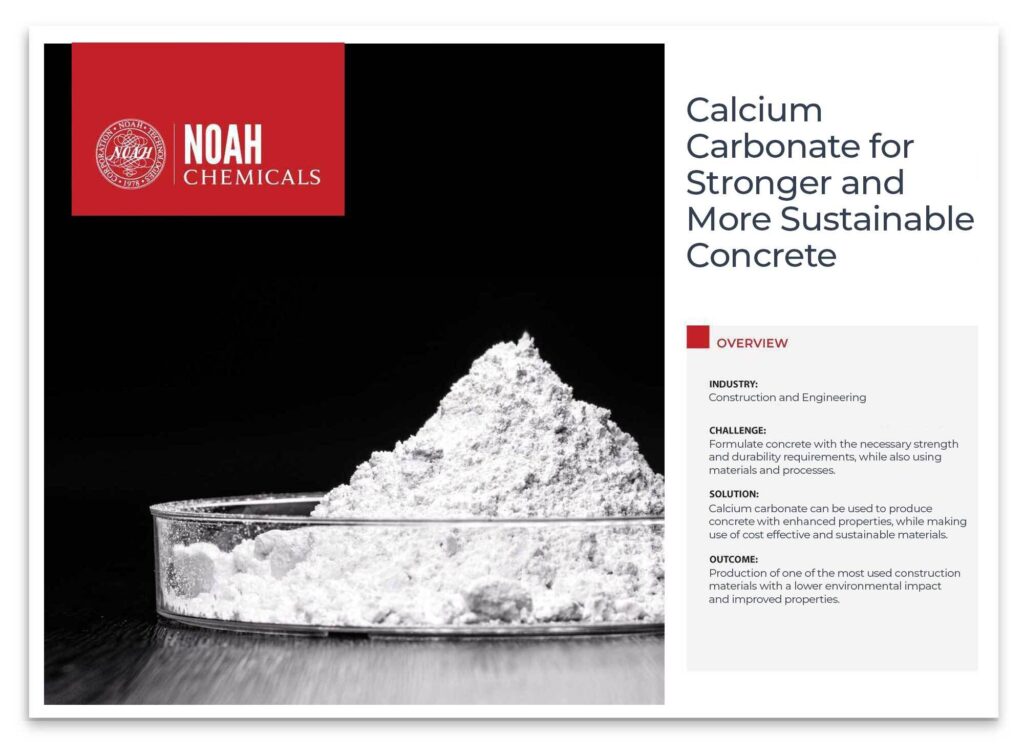

Chemical Quality and Purity

Quality and purity are crucial components in the efficacy and success of a given product. All materials are produced under strict quality control and quality assurance systems. Our chemicals and metals are available in various purities and particle sizes. Noah Chemicals is certified to ISO 9001:2015, DQS and our products are typically manufactured to meet high purity specifications ranging from 99% to 99.9999+%, in order to meet or exceed chemical regulatory grades for ACS, USP-NF and the FCC.

GLOBAL INDUSTRIES

Supplier of Choice to Fortune 500 Companies, Government Agencies and Laboratories

Noah Chemicals is an innovative, chemical solutions, chemical supplier and manufacturing partner for a broad range of clients. This includes Fortune 500 companies, government agencies, laboratories and business startups.

We manufacture an extensive list of research chemicals to scale and are a proven leader in creating custom products used in new and emerging technologies. Every project and client relationship is governed by The Noah Standard – our commitment to quality, innovation, results, partnerships, and accountability.

MANUFACTURING

Custom Chemical Manufacturing, Bulk Materials and Packaging

Our Chemists and Engineers enable the advancement of material science and new technologies. We collaborate with research facilities, agencies, and production companies to manufacture and supply specialized chemicals.

We offer consulting and technical assistance during the development process, as well as scaled-up quantities of special-quality materials. Additionally, we take specifications and application of small batch specialty products to bulk scale.

- Synthesis

- Formulation

- Consultation

- Blending

- Milling

- Calcining

MANUFACTURING

Synthesis and Formulation

We are experts in a variety of synthesis methods including purification, particle size reduction, calcination, combustion, and other synthesis methods from bench scale to bulk production. Our team has developed a proprietary crystallization method utilizing a multi-stage purification and dehydration technique for refining compounds such as fine powder crystals, hygroscopic salts, and other products.

In order to optimize pricing without sacrificing quality, our team begins each formulation with high purity reagents, intermediates, alkoxides, metals, inorganics, salts, and other ingredients. All aqueous solutions are prepared using ASTM Type 1 deionized water, and meet qualifications required for analytical titrants or atomic absorption standards.

SUSTAINABILITY

Our Dedication to Ecological Responsibility

Our belief in the importance of sustainable chemical production methods, or Green Chemistry, is a fundamental aspect of the Noah Standard. Our mission is to deliver innovative, high-quality solutions that benefit our customers, our industry and the Earth.

Solutions for Specialty Chemical and

Manufacturing Services

Manufacturing Services

Our Chemical Services team of experts have been collaborating with customers for 45 + years in order to bring innovative, chemical solutions to many industries and detailed analysis to a multitude of applications. We provide technical capabilities and expertise needed for all your unique chemical, material Application, Formulation, and Analysis. As a result, we have a strong understanding of new and continued development of the best materials required for robust process systems and finished goods.

- Inorganic

- Metal Salts

- Ceramics

- Rare Earths

- Alkoxides

- Intermetallics

- Evaporation Materials

- Reagents

- Metals

100+

Fortune 500 Companies

4000+

Products

Infinite

Custom Solutions

45+

Year History

60+

Countries

Chemical Quality

and Purity

Quality and purity are crucial components in the efficacy and success of a given product. All materials are produced under strict quality control and quality assurance systems. Our chemicals and metals are available in various purities and particle sizes.

Noah Chemicals is certified to ISO 9001:2015, DQS and our products are typically manufactured to meet high purity specifications ranging from 99% to 99.9999+%, in order to meet or exceed chemical regulatory grades for ACS, USP-NF and the FCC.

Supplier of Choice to Fortune 500 Companies, Government Agencies and Independent Laboratories

Noah Chemicals is an innovative, chemical solutions, chemical supplier and manufacturing partner for a broad range of clients. This includes Fortune 500 companies, government agencies, laboratories and business startups.

We manufacture an extensive list of research chemicals to scale and are a proven leader in creating custom products used in new and emerging technologies. Every project and client relationship is governed by The Noah Standard – our commitment to quality, innovation, results, partnerships, and accountability.

Custom Chemical Manufacturing, Bulk Materials and Packaging

Our Chemists and Engineers enable the advancement of material science and new technologies. We collaborate with research facilities, agencies, and production companies to manufacture and supply specialized chemicals.

We offer consulting and technical assistance during the development process, as well as scaled-up quantities of special-quality materials. Additionally, we take specifications and application of small batch specialty products to bulk scale.

Synthesis and Formulations

We are experts in a variety of synthesis methods including purification, particle size reduction, calcination, combustion, and other synthesis methods from bench scale to bulk production. Our team has developed a proprietary crystallization method utilizing a multi-stage purification and dehydration technique for refining compounds such as fine powder crystals, hygroscopic salts, and other products.

In order to optimize pricing without sacrificing quality, our team begins each formulation with high purity reagents, intermediates, alkoxides, metals, inorganics, salts, and other ingredients. All aqueous solutions are prepared using ASTM Type 1 deionized water, and meet qualifications required for analytical titrants or atomic absorption standards.

Our Dedication to Ecological Responsibility

Noah Chemicals is committed to environmental sustainability. We recognize the growing demand for safe, ethical chemical materials that maximize efficiency while reducing or eliminating waste. To that end, we continually strive to develop processes that meet or exceed global regulatory standards for environmental compliance.

Our belief in the importance of green chemistry is a fundamental aspect of the Noah Standard – our mission to deliver innovative, high-quality solutions that benefit our customers, our industry and our planet.

Our Dedication to Ecological Responsibility

Our belief in the importance of sustainable chemical production methods, or Green Chemistry, is a fundamental aspect of the Noah Standard. Our mission is to deliver innovative, high-quality solutions that benefit our customers, our industry and the Earth.

Noah Chemicals Insights and Case Studies

Discover perspectives from industry experts around digital transformation, trends, innovation, operations – all to help you determine your best path forward.

Hydrogen Gas and Two Powders Changing the Industry

It is widely known that the world is moving in the direction of green energy sources. Advancements in research are being made across more than just the wind, solar, and geothermal industries. Recently, two advancements in the production, storage, and transportation of hydrogen gas have been announced.

Read our Blog

Hydrogen Gas and Two Powders Changing the Industry

It is widely known that the world is moving in the direction of green energy sources. Advancements in research are being made across more than just the wind, solar, and geothermal industries. Recently, two advancements in the production, storage, and transportation of hydrogen gas have been announced.

Read our Blog

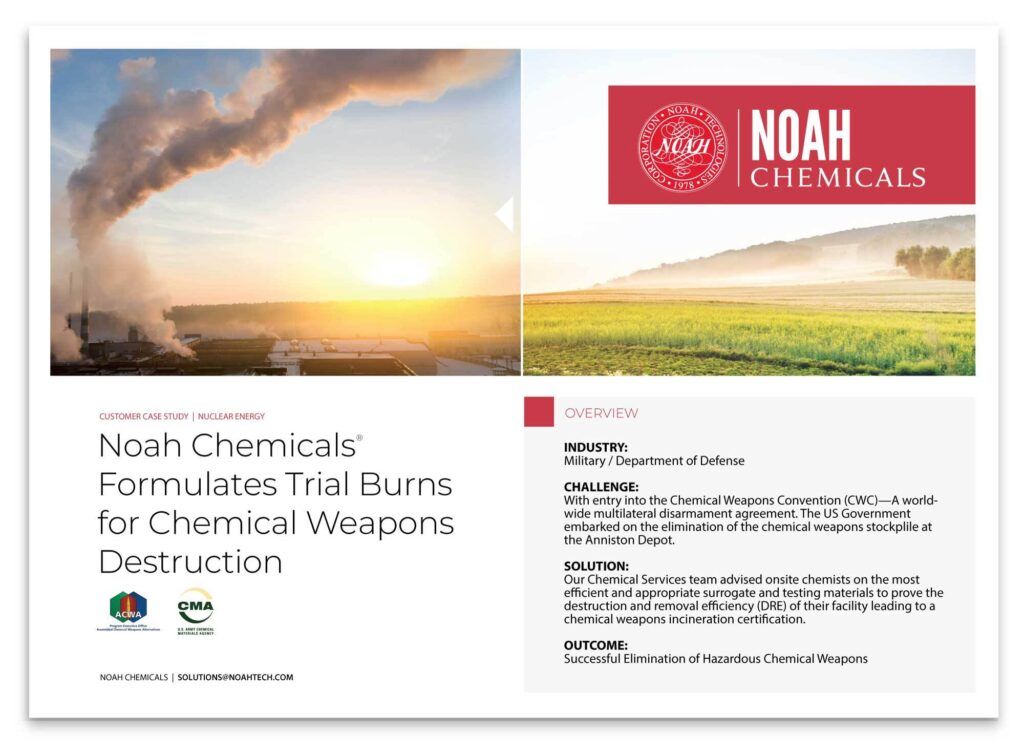

Trial Burns Case Study

We partnered with the US Army in developing efficient methods of testing the Destruction & Removal Efficiency (DRE) of their incinerator systems.

Download Our Case StudyWork with Us

Begin your partnership with Noah Chemicals to work at solving your most complex challenges.